The craft house of Vallein Tercinier boasts a family history that’s passed through five generations. From the founder, Louis Vallein, through Georges, Paul, and Robert, to Catherine Roudier-Tercinier who heads the house today, this is artisan production at its finest.

While we could wax lyrical about family traditions, Cognacs of distinction, and other elements that have brought the house to 2020, there’s nothing quite like being told the family story from one who’s actually lived it.

Our very own Max undertook the task of speaking to Catherine, discussing a tale that takes us from the late 1700s, through two world conflicts, the hardships of the post-war years, the tough times of the 1970s and 1980s, and into the golden era of Cognac that we’re living today.

We have to say, it’s a fascinating story. And there’s no-one better placed to tell us than Catherine herself.

Max: We’re going to talk about the history of the house. Tell me—who was the house associated with, in the beginning?

Catherine: Well, in the beginning it was Louis Vallein. He bought the property, called Domaine des Forges—it’s also called Le Point du Jour—in 1791. It was his son, Georges, who, in around 1850, decided to develop the vineyard. There were also cereals—crops—that we still have today.

Max: How many hectares do you have for crops and how many for the wine?

Catherine: We have around 130 hectares in total, and roughly 25 hectares of this is the vines. It’s actually my nephew who owns it right now, and he’s also purchasing new areas of vineyards too, so we’re expanding. He’s also developing another 80 hectares and replanting them to crops.

Max: What crops do you produce today?

Catherine : We have wheat, sunflowers, and rapeseed. We don’t plant corn because it requires a lot of water. We grow mainly traditional crops, but we might be forced to change this in the future because of global warming.

Max: I imagine the vines were grown originally for the production of wine?

Catherine: Yes, that’s right. Then my grand-father formed an association with a local distillery (Marcel Cottereau) and set up with four alembic pot stills. This was around 1930.

Max: This was in Barbezieux? Whereabouts?

Catherine: In a tiny place called Plaisance—it’s really small, not even a village, more like a property or hamlet. It’s near Saint Marie. When I started to work in the distillery my uncle was in charge. We produced eau-de-vie and sold it to Remy Martin.

Max: So does it mean that, back then, you didn’t have your own marque—your own brand name?

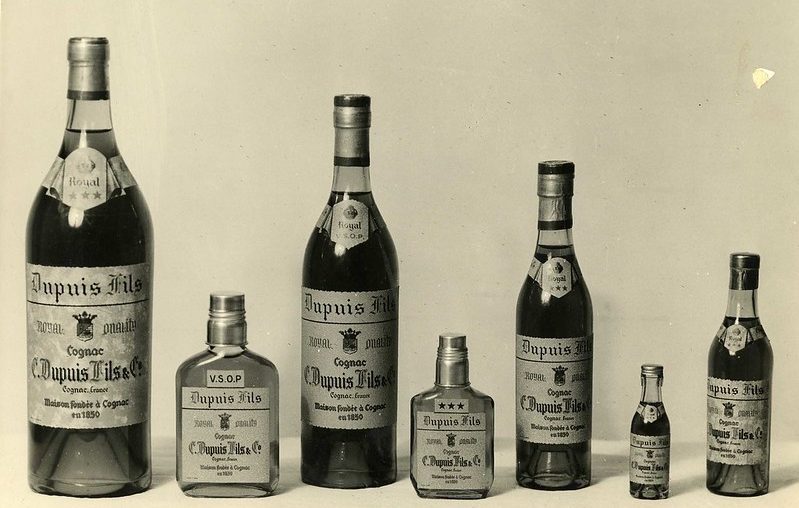

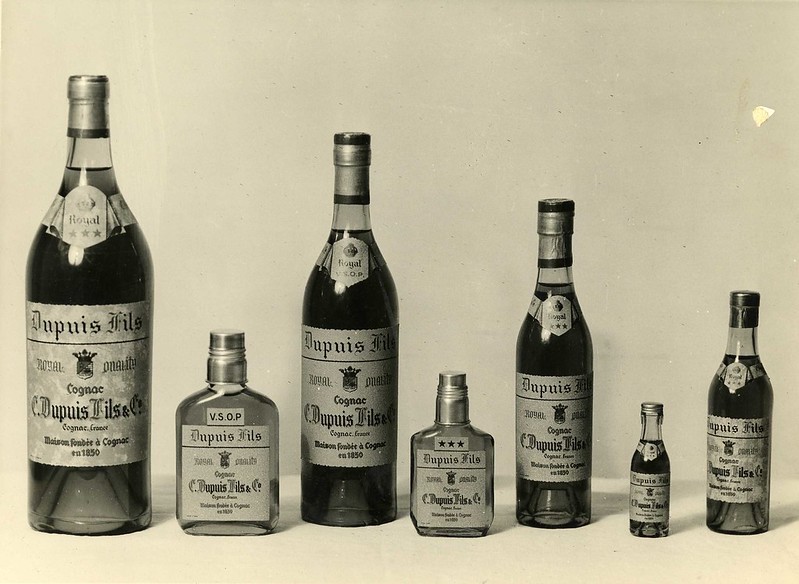

Catherine: We were working with our own brand and mainly producing and selling under the brand of Camille Dupuis.

Max: One shouldn’t mix it with the other Dupuy Cognac, owned by Bache Gabrielsen—it’s spelt differently.

Catherine: Yes, it’s a different brand. And Camille Dupuis himself was friends with Georges Vallein, my great grandfather. Georges was providing them with the Cognac and Dupuis was selling the bottles.

After that, I think it was around 1920, Paul Vallein bought the brand from Mr. Dupuis and we started to sell under the marque, Camille Dupuis.

Max: So why does the brand of Camille Dupuis no longer exist?

Catherine: Well, it does, but we can say we’ve put it out to pasture for the moment. Around 1986, maybe 1987, or so (I started the company in 1986), it was a little complicated. We were doing plenty of distillation but not producing many bottles. I really wanted to develop that part of the business—to produce more bottles. That’s when I figured out that it would be more interesting, more advantageous, to sell under our own name, rather than continue with the name Dupuis.

I wanted to keep the brand name of Camille Dupuis, just in case we needed it. I had many conversations about this with my father and… eventually I won!

The brand name has been with the family since 1920, so for 100 years now.

Max: So when did you stop selling Cognac under the name Camille Dupuis?

Catherine: I think we stopped in the 1990s. We continued to produce a pineau under the Dupuis name. There were two presentations—one under our name (Vallein Tercinier) and one under Camille Dupuis. In fact, we were selling more of the Dupuis pineau. But some people were saying that although the pineau was nice, the shape of the bottle wasn’t so popular. It was said to be rather Portuguese in style—I think that was a polite way of saying that the bottle was a bit ugly!

It was actually pretty complicated to have some products under the Vallein name and some under Dupuis. The two names made it complex and difficult to promote a clear brand. It gave us some marketing issues. So we decided to retire the name of Camille Dupuis—put it on standby, if you like. But we do have a few projects in mind for the brand. But we’ll talk about that another time.

Max: What happened between 1920 and the 1980s? What happened with the farming business? It was such an important period of European history.

Catherine: Well, my grandfather was an extremely modern man. He spoke French, German, English, he traveled a lot, was constantly on the lookout for new trends, always on the ball. At that time we used to distill for Courvoisier and Rémy Martin, etc. And we were also exporting in bulk (bulk selling)

My grandfather was an out and out businessman, whereas my father was a marvelous man, but not particularly business-minded. So, commercially-speaking, it was a fairly quiet period for the company during my father’s time. We did a lot of production for other Cognac houses, rather than looking to further develop the brand.

But it was also a very complicated period of history, so it was OK to concentrate on this, rather than pushing the brand and business.

Max: And it was still 20 hectares of vines?

Catherine: At that time we had 23 hectares and rented 12 more. We might have sold some of the vineyards during this volatile period. But now, my nephew’s aim is to re-develop and expand the entire vineyard.

Max: Let us talk a little bit about the vineyard. How old are the vines?

Catherine: We’re actually renewing everything. My nephew wants to replant the whole vineyard. Nothing had been changed since my grandfather planted the vines and he died in 1976. So, many of the vines were, or are, very old. My nephew’s already replanted over half the vineyard. Most of the vines are Ugni Blanc.

Max: So that’s 10 hectares. Did this re-planting take place recently?

Catherine: Yes, pretty recent. He started to work with us in 2010, so since then. Time is flying—it’s already 2020!

Max: And what is the Cru, the growth areas?

Catherine: So, in Chermignac we’re Bons Bois. Thenac and the surrounding villages are in the Fins Bois cru. Three quarters of our vines are in Fins Bois and a quarter in Bons Bois.

Max: And the Vallein-Tercinier L’ESSENTIEL Cognac I just tasted was from Chermignac?

Catherine: Yes, and we have a parcel of land, a plot, that produces exceptionally good Bons Bois eau-de-vie. It’s right next to the graveyard. It’s funny, because in the village this area is called “La Champagne” so it’s not a coincidence that it’s such great quality. Everything that’s grown from this particular plot of vines is really, really good. When you take very old Bons Bois Cognacs, vintage ones, and you taste the quality of it then you know you’re onto something really good.

Max: Meaning, this eau-de-vie has a taste almost like that from Grande Champagne?

Catherine: Yes, almost. Well, let’s be humble and modest—we’ll say Petite Champagne (laughs).

Max: With regards to vine replanting rights, you also received those 0.96 hectares of planting rights, as did all eligible Cognac winegrowers in 2020?

Catherine: Yes, the same as everyone else.

The War Years: a volatile period of history

Max: During and after WW1 the region was not too badly affected as it seems. But WW2 and Nazi occupation—that’s a different story…

Catherine: Yes, that’s right. WW2 was more complicated here—well, it was for everyone. We had the Germans here. They were actually staying in my grandparents’ house.

Max: At your grandparent’s house?

Catherine: Yes, my grandfather was the Mayor of the village. And my great Uncle, Paul Vallein, used to be the Mayor of Chermignac. It was a tough period for my Grandfather. He had to obey the Germans but he also had to protect his community. But there were no big dramas at home during that time. The dramas that occurred for us were during the liberation—right at the end and after the war.

This was because of a group known as La Compagnie Violette, who were treated as heroes. But in reality, most of them were robbers and criminals. They came and tortured and assassinated my great uncle, who was aged 80 at the time. They wanted to know where he’d hidden his money. It was terrible, a really harsh time. We were actually lucky that my grandfather was in prison at that time, as he was accused of being a collaborator—a traitor.

In fact, he was a very good man who had saved many people, But being imprisoned turned out to be a blessing in disguise, otherwise he would have suffered the same fate as my great uncle. The war was ugly. Having the Germans at home was not pleasant. But there was little violence—they made use of us to some extent. They took some of our belongings but we weren’t massively affected. There were no terrible events during this time—that came after the war.

Max: Rumor has it that the Germans went to Cognac and Bordeaux to pillage the wine cellars.

Catherine: Yes, it’s well known that this happened in Bordeaux. In Cognac we’re still trying to piece together exactly what happened. I never heard my grandfather or father make mention of any large scale theft. Of course, the Germans were helping themselves to the contents of our cellar, but not to any great extent.

I remember a story my father told me, where there was a German officer in his house. He had a son that was around the same age as my father—maybe 13 or 14—so of course he wanted to talk to my father. But my father and his sisters were forbidden to talk to any Germans. Of course, this is an anecdote.

I never heard my father or grandfather talk about theft from our cellars. But I guess the trauma to them and the family from what happened after the war—the murder of my great uncle—meant that perhaps these thefts seemed less important than they might’ve been.

Max: These liberators—were they the Resistance?

Catherine: Yes, some were from the Resistance, and many of them were really good people. But also, some of them were really bad people. They weren’t really for the cause, they never really helped. They had no morals about taking advantage of their status and, once they realized no-one would do anything about it, committing atrocities themselves. And there were a number of them in the region.

What happened to my great uncle—that happened to several people in the area. This is why we have our 1940 bottle of Bon Bois that we called “Hommage”, named in honor of my great uncle, Paul Vallein. It’s in memory of him and of the sad times that affected so many people during that period.

They tortured Paul in front of my father before they murdered him. So when my father occasionally had weird, or dark, thoughts, it’s pretty understandable, knowing that he went through such trauma.

Max: After the war, how did the family recover? How did they leave behind the trauma and make a more normal life?

Catherine: Well, my grandfather was a great man, full of energy. He had some friends—for example, the Maison Niox company, in Saintes, that sold bottled wine. He also worked with the company, Rouyer Guillet. He took up the business again, constantly working really hard, and searching for new things to do. My father came back and took over the business in 1947—or maybe a little later, he would’ve been too young then—perhaps the 1950s.

Max: And between the years 1960 to 1980, the family business was mostly working with Courvoisier and Rémy-Martin?

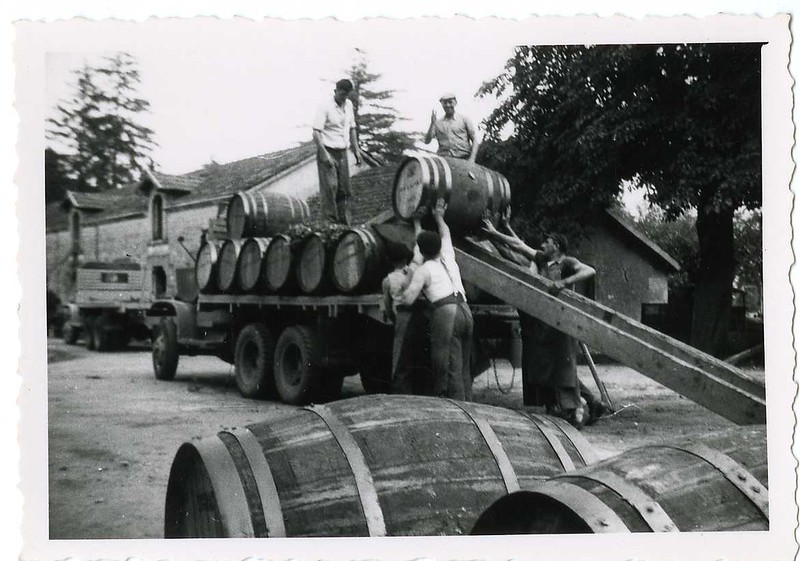

Catherine: Yes, exactly. It was the distillation, the vineyard. We were working for other companies, mostly. The bottling for Camille Dupuis was carried out at the distillery in Barbezieux at that time. We moved the bottling back home around 1975 or so, and Barbezieux distillery was sold.

It was my father who developed the bottle sales. They were not that many, so that’s why we took the opportunity to outsource.

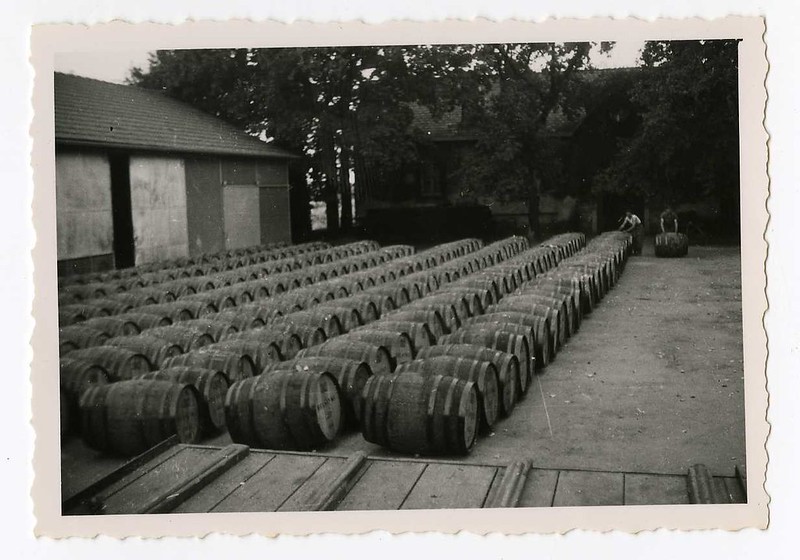

We had the distillery in Barbezieux and the distillery in Chermignac. We kept the one in Chermignac and expanded it after WW2. We had four alembic stills to begin with, and then expanded this to eight.

Max: That’s more than enough for 20 hectares of vines. I guess you outsourced quite a lot?

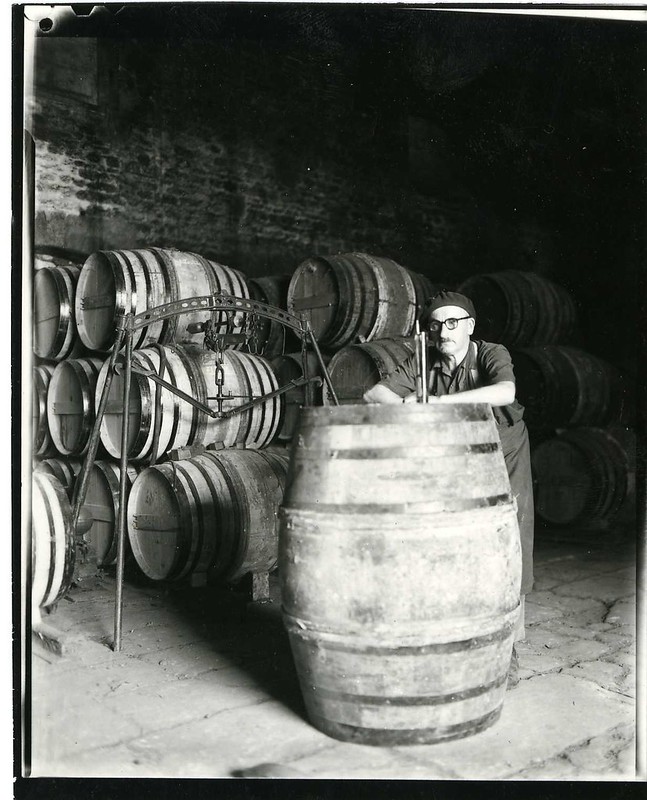

Catherine: Yes, we were buying wines and distilling them. Two alembics would be usually enough for covering 20 hectares of vines. I always say I’m lucky to have been born after the others. It’s thanks to their hard work that I have such great eaux-de-vie to work with. It’s all down to them and what they left to us.

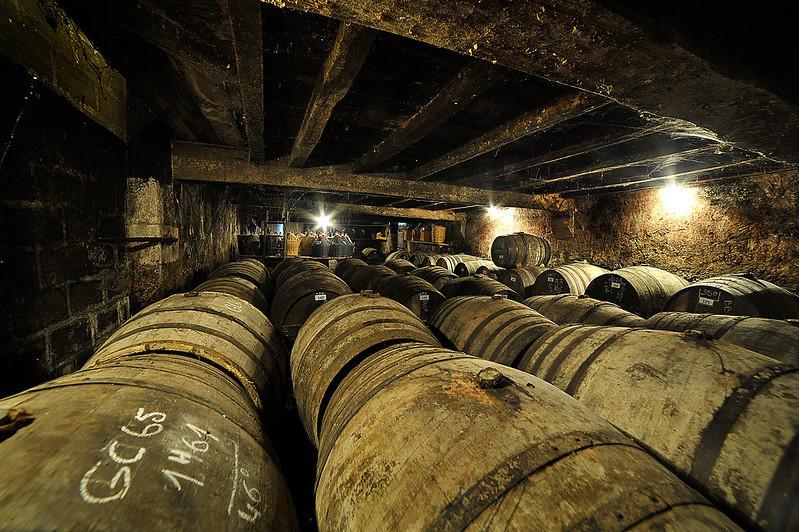

Max: And you still have a good stock of eaux-de-vie today?

Catherine: Yes it’s good because we’re a small business but we do a little bit of everything. This is what enables us to ride the hard times, like now—with COVID-19. When you’re small but diverse, it gives you the ability to bounce back.

Our cellar master Foucauld de Menditte is really well-respected and we also have a great taster.

Max: So you’re a winegrower, farmer, you distill with eight alembic stills and you carry out the bottling process too, right?

Catherine: Yes, we do that as well. We carry out all aspects, from the vines to the bottle, and we’re constantly improving the process. Right now, if we were to run at full capacity, we could produce 8,000 bottles per day. Not that we do, of course, but we have the possibility to do so. And we’re also a wholesale dealer.

Max: That’s a lot of different roles.

Catherine: True. But as I said, it enables us to diversify, reduce the risk, and allows us to be flexible, depending on what’s going on in the world.

Max: Over the last decade there’s been a real development of the brand, Vallein Tercinier. How did you get from the 1980s, and the brand Camille Dupuis, to today, with the brand Vallein Tercinier?

Catherine: We had our classic blend and we continued with the traditional qualities of VS, VSOP, Napoleon, XO, and Hors d’Age. We carried on with all of these, with the exception of the Napoleon, developing the brand of Vallein Tercinier during the 1990s.

We had a contract with Pierre Balmain, the haute couture fashion house that’s really well-known in Japan. This allowed us to network with importers with whom we’d never otherwise have had access to. Although we didn’t make huge sales, it opened up important links for us.

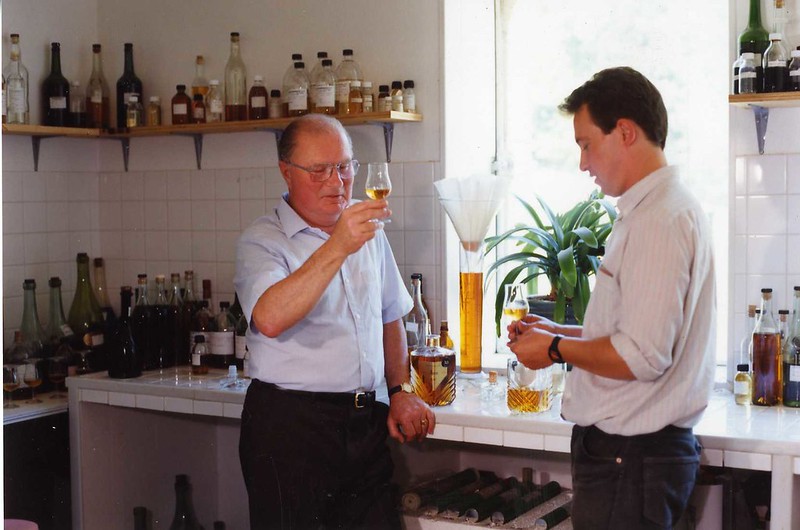

So we continued with our classic range. I was lucky to meet Pascal Baijot, from Maison Grosperrin, who’s a connoisseur of Cognac. He came to meet us to find out about our Pineau de Charentes. I gave him a tour of our cellar and he tasted our Grande Champagne that we call LOT 65. He said to me, “Catherine. You need to stop selling this in a blend and sell it on its own”. Well, he doesn’t like blends, but he was insistent that this Cognac should be sold on its own.

So I thought to myself, why not? At that time I was working with a sales person and I told her yes, let’s try it. This was 10 years ago, or something like that. So we introduced that to the maison du whisky and gave a sample to Serge Vallentin, who has a blog called Whisky Fun.

One morning I opened my computer and there were a load of email orders from all over the world for one particular bottle. It was really strange and I realized that something must’ve happened overnight. And it had… Serge had written a really nice review about LOT 65. As he has a lot of followers and influence it led to many sales.

So we began to take a closer look in our cellars to see if we had other Cognacs that were exceptional enough to be drunk as a vintage. This is how we began to produce our own range of brut de fut and millesime Cognacs. But we only want to do this with ones that are really, really special. We’d rather not put a new product on the market than launch one that’s not of the highest quality.

I think that during my grandfather’s time it was a really forward-thinking era. Then, when my father was in charge, it was much calmer. There was also the crisis during the 1970s. So when Vallein Tercinier was reborn we thought, now is the time to begin offering new products.

With whisky drinkers, in particular, there’s a lot of prejudice towards Cognac. Not that we’re asking them to switch allegiance, just to realize how good it is to drink and add to their repertoire. So, when we’re at the trade fairs, we persuade people who might not normally taste it to give it a try—even if they’re a bit reluctant. They might say they don’t like Cognac, so we tell them it’s probably because they’ve never tried a really good one.

We start by giving them a taste of a VSOP. This is usually met with surprise at how good it is. Then we move up in the qualities, and people often find it astonishing that a Cognac can be so good.

OK, so maybe I exaggerate a little, but this is pretty much how it goes.

The Renaissance of Vallein Tercinier

Max: This period, from 2010, we can call the Renaissance of Vallein Tercinier? Why the renaissance and why the name?

Catherine: Well, the Tercinier element came from my Grandfather, and the Vallein comes from Paul Vallein. So before the 1980s it was Camille Depuis. Afterwards it was reborn and became Vallein Tercinier.

Max: I’m guessing at the numbers here, that then you produced 10% for your own bottles and the rest for Remy Martin?

Catherine: Yes, it was exactly that. When I arrived, the production accounted for maybe 3% of our work. The rest was the distillation and the packaging—we barely bottled anything.

Max: What would you say is the percentage of bottling in the business today?

Catherine: For the brand of Vallein Tercinier it’s around 40%. And life always brings different elements. Sometimes it’s hardship or financial difficulties—I spent most of my first 20 years here trying to save the business. Making strategic decisions to enable us to pay the banks and not go under. Today we’re in a good position, the company is healthy. This means we can move forward, refurbish and carry out work, such as the replacement roof we’ve just finished.

But you know what saved me? When you have faith in what you’re doing and you believe in it? The bank was calling me every day… I felt like the whole family business was falling down around me. But in the cellar I found a Petite Champagne from 1935 that was truly marvelous. I poured a little bit into a glass each evening, after everyone else had left the office. My dad was still alive at that point, but I didn’t want to pressurize him. So I’d sit in the office with a small glass of this 1935 Petite Champagne Cognac, looking at pictures of my grandfather and great uncle. And I talked to them, saying, guys—we really need a break. We need something good to happen so we can carry on.

So I can say that the 1935 Petite Champagne is what kept me going and really, really helped me. It’s funny how you hold onto the little things when the going gets tough. I still regularly talk to my grandfather, great uncle, and father to discuss the business and ask for help as we move forward. And I’m convinced that they do!

Max: That’s a superb ending. Catherine, thank you for the interview.

The article was created with Jacki’s assistance.