On the face of it, Cognac as a spirit is actually quite simple. A producer grows grapes (mainly ugni blanc), makes a white wine, distills it twice, stores the distillate in new or used oak barrels, and waits. But that is only on the face of it. To say the story ends there would be a massive oversimplification of how one of the world’s most complex spirits is actually produced. The amount of variables, external factors, and human interventions that can impact what ultimately ends up in the bottle is staggering.

And so while there are so many factors to zero in on, the particular focus of this article is on the alcohol reduction process, that is, the spirit’s journey immediately off the alambic at say 71% alcohol down to a bottling strength of 40% or 43%, or other.

I am not a Cognac producer nor do I pretend to possess even a fraction of the experience required on how to reduce a Cognac. But, I have been fortunate to visit a lot of producers and ask them questions on this vital step of the Cognac production process. My wish is to explain what are some of the different ways producers bring down the alcohol level of their Cognacs. This topic flies under the radar but deserves attention, since so much can happen, and so much goes on, between a Cognac’s still strength and its bottling strength.

The Wine and the Distillate

Let’s quickly recap some of the key rules about what can be distilled and the distillate itself following distillation. The AOC Cognac Cahier des Charges – think of this like the official Cognac production rulebook – in Section D. – Description of the production method, Part 7 Analytical criteria of the product to be distilled states, “At the time of distillation, the wines have a minimum alcoholic strength by volume of 7% and a maximum alcoholic strength by volume of 12%. Their volatile acidity content is less than or equal to 12.25 milliequivalents per liter.” This essentially establishes a sort of window – albeit a large window – for the alcohol level of the wine that will go on to distillation. Therefore, the wines must be between 7 and 12% alcohol.

Then, the double distillation process occurs in an alambic Charentais, and at the end of the second distillation, the spirit that drips from the still must not exceed 73.7% alcohol (a number that was officially increased a few years ago from 72.4%). The rulebook in Section D, Part 8d. states, “After double distillation, the alcoholic strength by volume of the spirits must not exceed 73.7% at 20°C, in the daily spirits container.”

So to put it simply, the wine is loaded into the alambic at roughly 10% alcohol and leaves the still after two distillations somewhere between 70 and 73% alcohol. From the moment the eau-de-vie leaves the still and enters either new or used oak barrels, the alcohol level will reduce over time, either naturally or with a little boost from a cellar master armed with water. Producers can use demineralized water, distilled water, or reverse osmosis water to reduce, or dilute, the alcoholic strength of the spirit. It is also said that a producer can use recycled rainwater for the reduction, provided that the rainwater was recovered at the estate itself. There is a final option called “les petites eaux” which will briefly be discussed below.

Let the Angels have their share

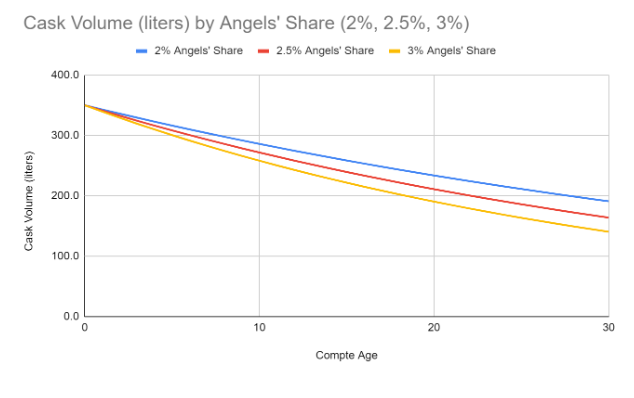

For the period of time – in some cases many years, even decades – eaux-de-vie spend aging in new or used oak barrels, they lose a significant portion of their liquid volume due to evaporation into the surrounding atmosphere. This is commonly known as the Angels’ Share. Take a moment to digest some numbers directly from the Bureau National Interprofessionnel du Cognac (BNIC) website: According to 2022 stock counts, there was the equivalent of 2 billion bottles worth of Cognac aging in oak barrels in cellars throughout the Cognac region. If we assume an annual Angels’ share (evaporation) of 2-3%, which tends to be a regional average, that translates to the equivalent of 40-60 million bottles of Cognac lost to evaporation per year.

The graph below simulates 2%, 2.5% and 3% angels’ share for a 350 liter cask. For simplicity, it assumes that the cask is filled to capacity – so no headspace – and that there is no topping up of the barrel. As we can see, for all three angels’ share simulations, at 30 years of aging, there is roughly half of the Cognac left in the barrel.

It is essential to point out that the Angels’ Share refers to the evaporation of liquid into the surrounding atmosphere. An Angels’ Share of 2% does not mean that the alcohol level is decreasing 2% per year. What evaporates, seemingly vanishing into thin air, is alcohol, water, and other volatile compounds in the aging Cognac. Each will evaporate in different proportions and at different speeds, depending on a variety of factors. More on that in a second.

In the examples above, at the youngest compte age, the eau-de-vie would have an alcohol level of roughly 70%. Therefore, in this example that means 245 of the 350 liters are pure alcohol and 105 liters are water. During the evaporation process in which the Angels take their share, alcohol and water are both escaping through the barrel, in addition to other volatile compounds. But the rate at which they are evaporating into the surrounding environment is not necessarily the same.

It would be convenient to write off these angels as simply being greedy, but that is not the case. This evaporation has a major and positive impact on the Cognac’s aromatic profile and overall complexity. But what needs exploration are some of the factors that play an important role in this evaporation, and in particular how much the angels take and in what proportions?

The non-exhaustive list below gives several factors that will influence the Angels’ share, and in particular how much alcohol, water, and volatile compounds are evaporating from the barrel:

- Air temperature in the chai

- Humidity in the chai

- Air pressure

- Cask volume

- Grain of the oak

- Porosity of the oak

- Stave thickness

- Fill level and/or headspace

- Earthen or concrete floor

- Stacked barrels or not

- Roofing material

- Air circulation in the chai

Let’s quickly explore some of these.

Environmental & chai conditions

The impact of temperature and humidity on the evaporation process in Cognac aging is hugely important, with each factor playing a role in the oak barrel’s interaction with its surrounding environment – in this case the aging cellar, or chai. High humidity levels in the chai decrease water evaporation from barrels, as the surrounding air is already saturated with water.

In other words, in a high humidity chai (roughly 90-100% humidity), the atmosphere of the chai already contains a significant amount of water vapor, so the alcohol will evaporate more than the water. In contrast, dry chai conditions enhance evaporation rates due to the air’s ability to absorb more moisture. If there is less water vapor in the chai atmosphere, then it can absorb more moisture by way of evaporation.

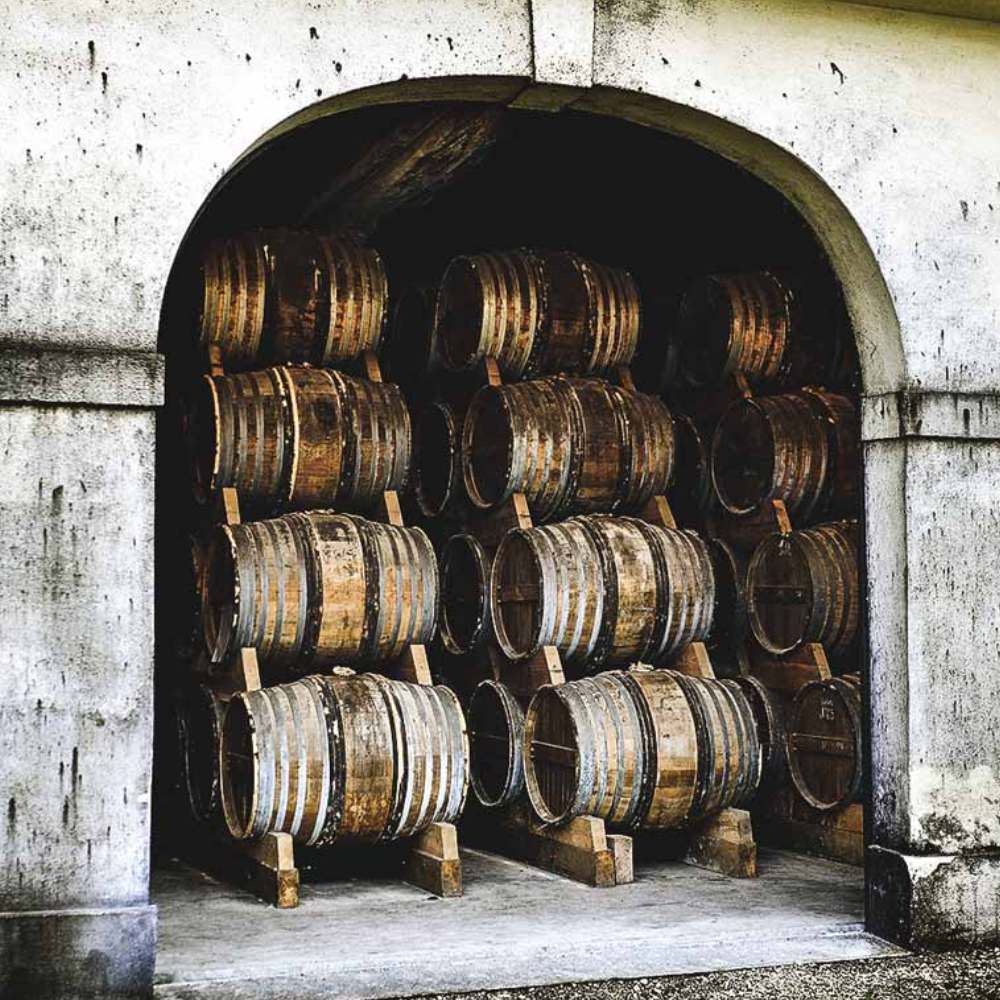

Temperature increases lead to higher evaporation losses of both alcohol and water, so the share the angels take is seasonal to some extent: their share will vary from the bone chilling winter cold and scorching hot summer days. However, traditional earthen chai with thick stone walls, with their high humidity and stable relatively cool temperatures keep these evaporation fluctuations down. By contrast, the highly variable conditions in modern racked maturation warehouses are more susceptible to external temperature fluctuations due to their construction materials and design. And what’s more is that these warehouses sometimes are stacked ten barrels high, so a barrel’s relative position in the warehouse will play a role. The barrels stacked highest will likely see greater evaporation than those tucked on the bottom levels.

For these reasons it is always so important and interesting to ask producers what kinds of cellars they possess and how they manage the development of their eaux-de-vie by transferring Cognacs from one cellar to another as needed. It is not as simple as just setting fresh spirit in a barrel, tucking it in some corner of the cellar and then waiting for 20, 30, 40+ years. Most eaux-de-vie need to be accompanied throughout their maturation process, and this involves the cellar master to know precisely which cellar type and cask type, amongst so many other things, will be the best for the Cognac.

But it’s true, this dry vs humid cellar is one of the most fascinating topics in the Cognac production.

Barrel properties

While temperature and humidity are two of the biggest factors affecting the angels’ share, the properties of the actual barrel certainly play a role as well. Cask size, cask grain (fine or wide), cask chauffe, cask porosity, cask stave thickness, and the chosen fill level or headspace amount all have an impact. Each of those properties affects how the spirit interacts with the wood, so naturally this impacts the angels’ share.

Reduction Techniques

The following techniques represent different ways in which a producer can reduce the alcohol level of a Cognac. Each of these come from the mouths of actual Cognac producers. But one thing is for sure: the Cognac region is immensely diverse, and that includes diversity of style and diversity of opinion.

A common denominator amongst all of the processes below is that it takes time to reduce, or dilute a Cognac, and in most cases a considerable effort is made by the producer to add the water early on and in the smallest amounts possible to give the Cognac proper time to marry. Rushing this step can result in Cognacs with off aromas and an overall lack of balance, among other things. Some even say the Cognac takes on a soapy character.

A few quick calculations

Before exploring a small handful of reduction techniques, it might be wise to have an idea of how much water needs to be added to take a Cognac from its current alcohol level to some defined target alcohol level. For simplicity, the table below assumes there is 1 liter of Cognac at its current abv level. The calculation is therefore for how much water would need to be added in one shot to reach the desired target abv. Obviously, for a very high current abv level, more water would need to be added to reach 40%. Contrariwise, for a Cognac that is already approaching 40%, only a small amount of water is required to make the final reduction. What are the amounts?

Current ABV % | Target ABV % | Amount of Cognac (Liters) | Amount of water to add (Liters) |

65.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.625 |

64.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.600 |

63.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.575 |

62.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.550 |

61.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.525 |

60.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.500 |

59.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.475 |

58.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.450 |

57.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.425 |

56.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.400 |

55.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.375 |

54.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.350 |

53.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.325 |

52.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.300 |

51.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.275 |

50.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.250 |

49.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.225 |

48.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.200 |

47.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.175 |

46.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.150 |

45.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.125 |

44.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.100 |

43.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.075 |

42.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.050 |

41.00% | 40.00% | 1 | 0.025 |

And just for the sake of having a second example, suppose now that a producer wants to bottle a Cognac overproof but with a small reduction to make the Cognac slightly more accessible in terms of its alcohol level – so overproof, but not cask strength. Imagine that the Cognac is currently at 52% abv and that the producer considers bringing it down to 48%, 47%, or 46%, but not below that amount. The amount of water needed to be added is in the table below.

Current ABV % | Target ABV % | Amount of Cognac (Liters) | Amount of water to add (Liters) |

52.00% | 48.00% | 1 | 0.083 |

52.00% | 47.00% | 1 | 0.106 |

52.00% | 46.00% | 1 | 0.130 |

The above examples – perhaps oversimplified – simply show the quantity of water that needs to be added to 1 liter of Cognac to reach a desired alcohol level. The reality is that the process for bringing a Cognac’s alcohol content down is very precise and done slowly in small increments. It is never as simple as dumping in a required amount of water, stirring and bottling. The reduction techniques below will give a slight view into some of the different ways in which a producer can dilute the strength of a Cognac.

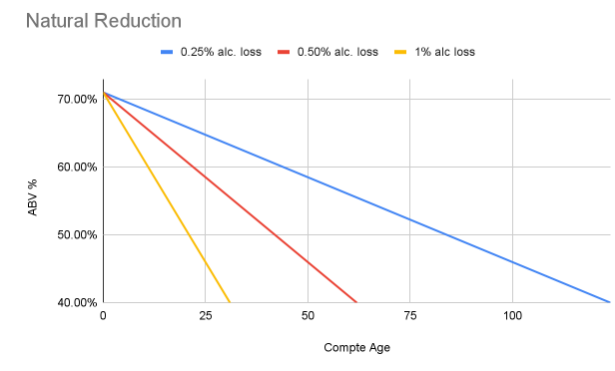

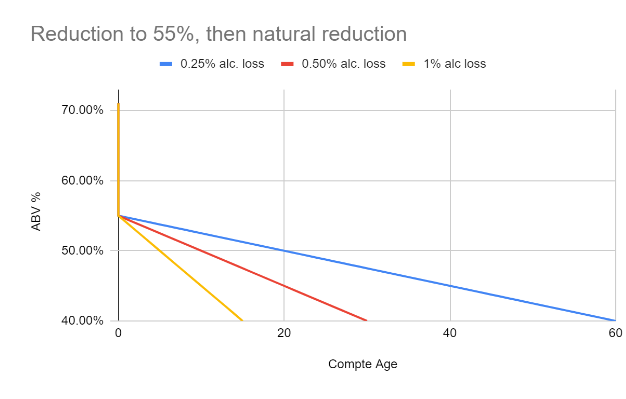

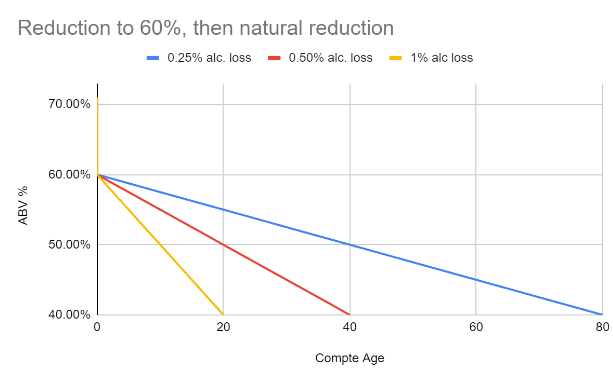

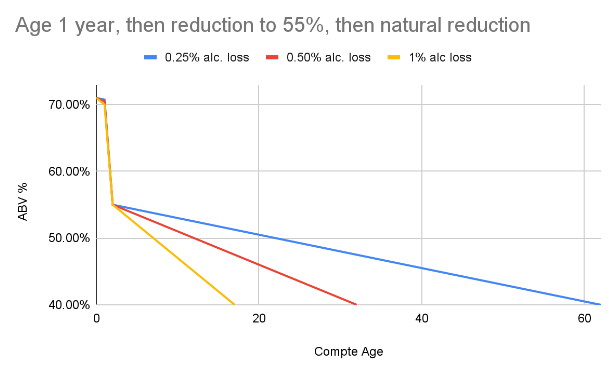

Please note that the graphs assume an alcoholic strength immediately following distillation of 71%. And the graphs assume the alcohol loss per year (%) is constant. Alcohol loss is anything but constant since it depends on so many of the constantly fluctuating factors described above, but for the sake of obtaining graphs and getting a glimpse of these reduction techniques, the decision was made to allow the alcohol evaporation rates to be constant.

Natural Reduction

This is exactly as the name would suggest: a natural reduction with no water added whatsoever. That is, the alcohol level reduces over time via the evaporation of alcohol as a proportion of the angels’ share. In humid cellars, a Cognac could feasibly reach the low 40%’s after 40 years of aging, but in a very dry cellar, the Cognac could feasibly remain in the high 60%’s at the same age. As an example, earlier this year I was speaking with someone who had a 1990 Fins Bois, still in barrel at 69% abv. The graph below shows natural reduction cases for three different alcohol evaporation rates per year:

Reduction to 55% at compte 00, then natural reduction

Immediately following distillation, the producer reduces to eau-de-vie down to 55% alcohol. Then, a natural reduction would occur until bottling. Of course, for younger bottlings, several incremental reductions would be needed to reach a 40% bottling strength. This is reality for all VS and VSOP Cognacs. There is just no other way to reach 40% in such a short amount of time. But for the producer’s older Cognacs, the Cognac could reduce naturally from 55% to bottling strength, even if that bottling strength may be 40%. In 25 to 35 years it can be done, and the beauty is that the Cognac put in bottle, although reduced with water early on, would not have seen a drop of water over the last 25 to 35 years.

The graph below shows this reduction technique for three different alcohol evaporation rates per year:

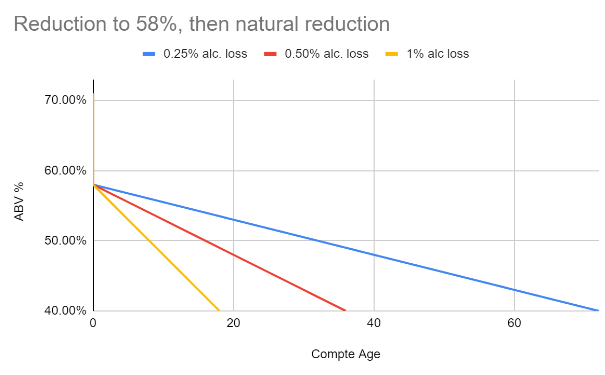

Reduction to 58% at compte 00, then natural reduction

Reduction to 58% at compte 00, then natural reduction

Same philosophy as the technique above but the initial cut is to 58%. Our dear neighbor Jacques Petit tended to adhere to this technique for some of his Cognacs.

The graph below shows this reduction technique for three different alcohol evaporation rates per year:

Reduction to 60% at compte 00, then natural reduction

Same philosophy as the technique above but the initial cut is to 60%. Some of the Vallein Tercinier Cognacs are reduced this way.

The graph below shows this reduction technique for three different alcohol evaporation rates per year:

No reduction from compte 0 to compte 1, reduction to 55%, then natural reduction

Here, no alcohol reduction is done for the first year of the spirit’s life, so from compte 00 to compte 1. Then a reduction down to 55% is performed – in small increments over the period of one year – followed by a natural reduction thereafter. This is not significantly different from the “Reduction to 55% at compte 00, then natural reduction” process highlighted above, but it allows the eaux-de-vie to settle for one year off the still and in barrel before receiving water to dilute down to 55%. The producer in mind with this technique feels that first year off the alambic is important for the spirit to settle down and receive its first contact with wood, generally newer oak in that first year.

The Claude Thorin Lot 90 Folle Blanche was handled in this way, for example. The red line in the graph below demonstrates the likely development of the Lot 90’s alcohol level, given that it is a 33 year old Cognac today, bottled in late 2023 at 40% alcohol.

The graph below shows this reduction technique for three different alcohol evaporation rates per year:

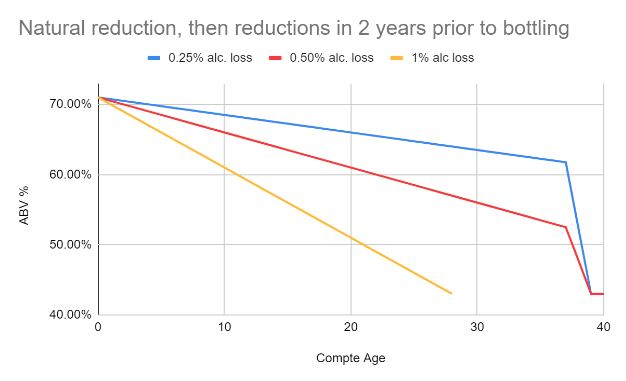

Natural reduction, reduce in 5% increments 2 years before bottling

As the name suggests, a natural reduction leads the way. Then, two years prior to bottling – regardless of if it’s for a 6 year VSOP or a 40 year old Hors d’Age – small incremental reductions are performed. Generally speaking, a producer will never reduce more than 5% at a time. But essentially, the producer has two years to space out the water additions to reach the desired bottling strength.

Cognac Grateaud reduces its Cognacs this way. When we were at the domaine tasting in the chai, we were able to taste the future Napoleon and the XO as they had begun their reduction process.

The graph below shows this reduction technique for three different alcohol evaporation rates per year. Let’s assume it is for a 40 year old Hors d’Age Cognac bottled at 43%. We see that in a cellar with 1% alcohol loss per year (yellow line), realizing this 40 year old Hors d’Age Cognac is not possible. The producer would have to move that Cognac to a dry cellar, where the conditions would allow aging to continue but with a slower rate of alcohol loss until 40 years old.

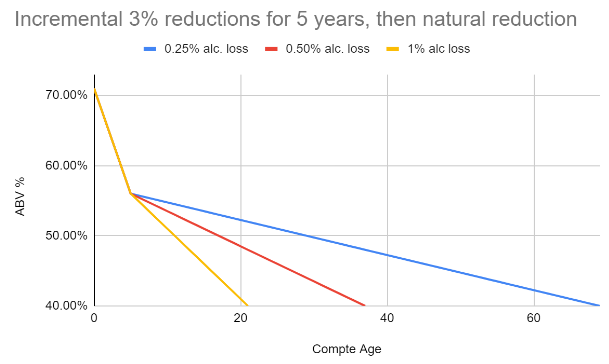

Incremental reductions from compte 00 to compte 5, then natural reduction

This process essentially says that all small and incremental alcohol reductions are done in the first five years. After that point, the Cognac is left to age and reduce naturally until bottling. It would seem that this approach only applies to special series of bottlings – like a vintage range, for example, and not a standard range of VSOP, XO, etc. In other words, it seems destined for Cognacs that will age for a certain amount of time – say 20, 30, 40 years and beyond.

Giboin in the Borderies does indeed work in this way with their vintage range. Interestingly, they release one barrel at 20 years of age and another barrel at 30 years of age. With this reduction technique, the Cognac gets into the 44-48% alcohol range, and most importantly has not seen an addition of water for 15 and 25 years respectively.

The graph below shows this reduction technique for three different alcohol evaporation rates per year: Reduction with les petites eaux

Reduction with les petites eaux

It’s tough to get a single definition for Les Petites Eaux, which translates in English to “the small waters.” I have heard of it as very old mature Cognac that has dipped below the 40% alcohol level, and therefore cannot be sold since 40% is the strict minimum. A producer surely would not discard such old and rare treasures. I’ve also heard that Les Petites Eaux is water that is aged for decades in oak barrels that previously held Cognac, therefore gaining color, alcohol content, and complex aromas and flavors.

The idea with this rare but fascinating reduction technique is that the addition of Les Petites Eaux very slowly brings down the alcohol level, since it is lower in alcohol than the Cognac is being reduced in the first place. And it does so in a very gentle way since les petites eaux themselves are so complex. In fact, the resulting reduced Cognac gains in complexity and the underlying objective of bringing down the alcohol level is reached.

Drip-by-drip reduction

A final technique I have heard about but rarely see is a drip-by-drip reduction. Think of this like as IV bag drip for a batch of Cognac. In determined intervals literal drops of water are added and then allowed to marry, or integrate, with the Cognac in the batch before another drip comes. So while there is a regularity to the addition of water, it is done in micro quantities so the Cognac has all the time it needs to fully settle.

So many more…

I cannot stress enough that the above list is not exhaustive. For every reduction technique presented here there is likely a handful that are practiced and defended throughout the Cognac region. What I’ve come to find is that Cognac producers generally have no problem talking about their production techniques, so if one poses a question about the reduction process, it will likely be met with a detailed precise reply and strong defense of why that way of proceeding is THE best way to make Cognac.

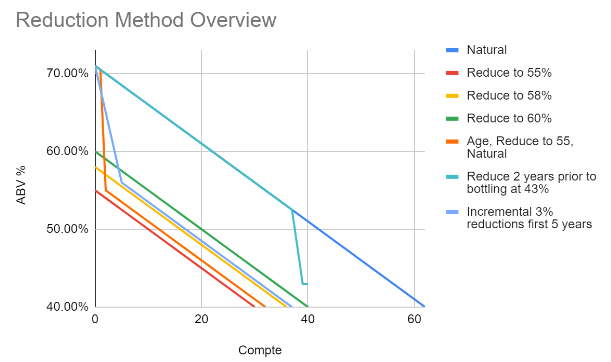

Here is a final overview graph showing all of the above reduction methods, excluding les petites eaux and drip-by-drip. The assumption is the spirit left the still at 71% and is in a cellar that loses 0.5% alcohol per year, in addition to what other proportions of water and volatile compounds the angels also decide to take.

What not to do

A word should also be said about what is NOT a common practice with Cognac producers, and that is reducing the alcohol level by adding a significant quantity of water in one shot immediately prior to bottling. We have not encountered a single producer who has not suggested some sort of incremental and slow process in how the alcohol level is reduced – regardless of whether the Cognac to be bottled is a four year old VSOP or 50 year old family reserve.

Like the aging of a fine Cognac itself, the reduction takes time and requires patience. Let’s not forget the regional animal is Cagouille Charentaise (a type of snail) – always slowly moving forward, never backward.

Conclusion

The goal of this exploration of reduction was to explain what it is, what are some of the factors that impact how a spirit may reduce naturally, and explain some reduction techniques practiced by producers today. If unlimited time resources were at my disposal as well as full access to many different professionals in the region, it could be interesting to learn more about the physical process of the angels’ share, the chemistry and the interaction between the spirit, wood, and the surrounding environment. And I would love to poke around from chai to chai picking producers’ brains about this all important step. But for now, this exploration will suffice and will hopefully give a reader an idea of one of the most meticulous production steps a Cognac producer has to complete.

Whether you enjoy your Cognac at 40% bottling strength, slightly overproof at say 43%, or high intensity cask strength naturally reduced Cognacs in the low 50%’s you may now know that there is a lot that goes on to get that Cognac from its 70-73% strength off the alambic down to what’s in the bottle. The angels do indeed take their healthy share, but man is undoubtedly able to leave a mark on the final product. Cheers to that!